Inspired by Prof. K. V. Krishna Murthy — Deeply rooted in ancient Indian mathematics, cosmology, and sacred science. From the earliest hymns of the Veda to the academic halls where modern historians study them, mathematics in ancient India was not a detached intellectual pursuit — it was a living part of culture, ritual, and cosmic understanding. In this article, we explore the heart of that tradition: how Vedic geometry emerged, why thinkers like Prof. K. V. Krishna Murthy saw it as fundamentally connected to time and space, and how it influenced everything from astronomy to architectural science.

- Time, Number, and Space — A Vedic Synthesis

- Śulba Sūtras: Geometry Born of Ritual Precision

- Geometry and Mathematics Beyond Ritual

- Decimal Systems Long Before the West

- Mathematical Sciences in Post-Vedic Literature

- Geometry as the Language of Reality

- Eminent Figures in Vedic Mathematics

- Sulba Sutras In Glimpse & Conclusion

Imagine a scholar who embodies the grace of Lakshmi and the wisdom of Saraswathi, purified by Shiva’s benevolent gaze. His virtues expand, drawing admiration from peers, while he captivates the minds of intellectuals. This metaphorical tribute, penned by an ancient author, celebrates the mathematician who delves into the ocean of numbers, surpassing all in wisdom and kindness.

Mathematics, at its core, is pure logic. Historical evidence shows that advancements in mathematical sciences invariably propel physical sciences forward. To gauge a nation’s scientific prowess at any era, one need only examine its mathematical landscape—the rest follows suit. Just as mathematics underpins physical sciences, logic forms the bedrock of philosophy. Where logic thrives, mathematics flourishes. The key distinction? Logic uses everyday language, while mathematics employs numerals and geometric forms.

Ancient Indians, masters of diverse sciences, held mathematics in sacred regard. A compelling proof comes from Vedanga Jyotisha, dating back beyond 1200 B.C, while few scholars state it dates to somewhere between 1400–1100 BCE based on astronomical references in the text.

Just as the natural feather on the head of a peacock and just as gems on the head of a divine serpent, Jyotisha – the science of astronomy is placed on the head of the other sastras – so says the well known Vedanga Jyotisha.

In the Bhagavad Gita, Lord Krishna declares:

विद्यानां गणितं मुख्यं कलनं संकलनं व्यकलनं

As interpreted by Sri Adi Guru Sankaracharya, कलनं संकलनं व्यकलनं represent the foundational aspects of गणनं. संकलनं signifies addition, and व्यकलनं denotes subtraction. Multiplication emerges as streamlined addition, while division is efficient subtraction. No matter how advanced mathematics becomes, it remains anchored in these core operations—ultimately, just addition and subtraction.

This leads to an intriguing equivalence: Time equates to Astronomy, which in turn equals Mathematics. Yet, one might question this, noting that time uses numerical representations, while astronomy involves geometric shapes. How can they align? Astronomy, as the study of time, incorporates both numerical and spatial elements. Mathematics divides into two inseparable branches:

- Mathematics of Numbers: Focused on quantities and calculations.

- Mathematics of Space: Dealing with lines, curves, and forms.

The mathematics of time handles numerals, whereas spatial math explores geometry. Since time and space are intrinsically linked—as affirmed in both ancient and contemporary theories—these branches converge at their essence. The Vedas, which probe the “ultimate” from multiple viewpoints, naturally encompass numbers, space, and the mathematics uniting them.

Time, Number, and Space — A Vedic Synthesis

When the Bhagavad Gītā and later commentators like Śankarācārya discuss calculation (gaṇana), they point out its fundamental operations: addition (saṅkalana) and subtraction (vyavakalana) — and by extension, multiplication and division. These, Prof. Krishna Murthy noted, form the entire universe of mathematical operations. In the Vedic conception:

Time = Astronomy = Mathematics

This is more than a poetic claim. In ancient India, the science of time measurement — Jyotiṣa — was grounded in celestial observation and numerical calculation. Unlike modern astronomy, which treats math as a tool, the ancient view saw mathematics itself as an expression of cosmic time and geometry embodied in the motion of celestial bodies.

Thus, numbers are not abstract tokens but are reflections of measurable reality — rhythms of sun, moon, and stars — and tied inherently to space with its lines, curves, and dimensions.

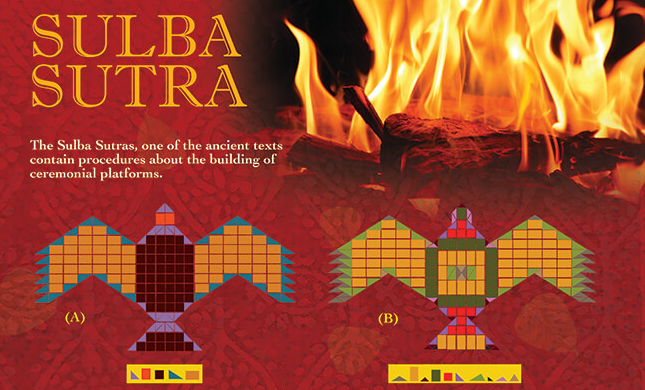

Śulba Sūtras: Geometry Born of Ritual Precision

Among the most remarkable expressions of ancient Indian mathematical ingenuity are the Śulba Sūtras — geometric manuals that emerged between roughly 800 BCE and 200 BCE.

The word Śulba literally means “cord” or “measuring rope.” Unlike later geometry texts from Greece, these were not theoretical treatises, but practical guides written to ensure that sacred altars used in Vedic rituals were constructed with precise proportions. Every shape had religious significance — and accuracy in construction was essential to the ritual’s spiritual efficacy.

|  |

According to historians, Śulba geometry contained:

- Rules for constructing squares, rectangles, circles, and other shapes

- Exact procedures for converting one shape’s area into another

- Use of Pythagorean triples centuries before Pythagoras himself

- Early evidence of irrational numbers and quadratic forms

For example, the Baudhayana Śulba Sūtra — among the oldest known — describes how to construct a square equal in area to a given rectangle using only a rope and stakes.

Geometry and Mathematics Beyond Ritual

While the Śulba Sūtras anchored geometry in sacred construction, their influence spread into later mathematical and astronomical sciences. Subsequent Indian thinkers such as:

- Āryabhaṭa — whose Aryabhatiya wove together mathematical computation and astronomy in the 5th century CE

- Brahmagupta, Bhāskara II, and others — who expanded arithmetic, algebra, and astronomical computation

built upon geometric foundations that had roots in Vedic practice. Scholars have even argued that certain trigonometric ideas and infinite series concepts developed later in the Kerala School of Mathematics reflect an intellectual lineage that can be traced back to earlier geometric intuitions cultivated in Vedic contexts. An early and authoritative testament to this reverence appears in Vedāṅga Jyotiṣa, a text dated earlier than 1200 BCE. It famously proclaims that Jyotiṣa (astronomy) stands atop all sciences, just as:

- A peacock bears its feather

- A divine serpent carries a gem upon its hood

This imagery emphasizes that time, astronomy, and mathematics are inseparable sciences.

Decimal Systems Long Before the West

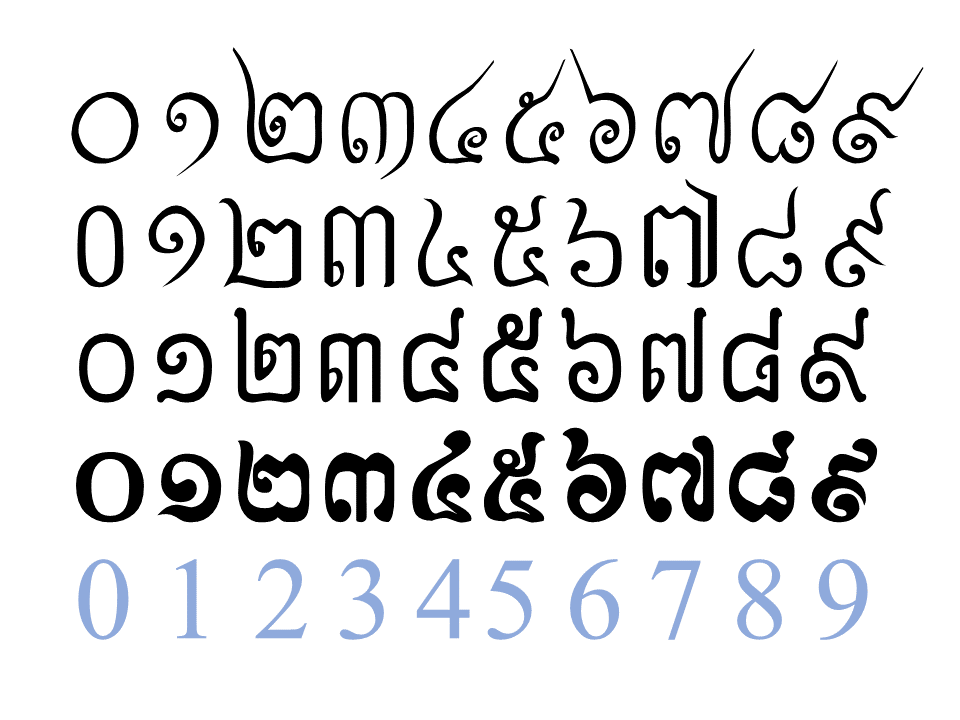

Pythagoras, in the 3rd century B.C., attempted to quantify sand particles in his “The Calculus of Sand” but fell short of a complete decimal system, lacking the concept of zero. Contrast this with Vedic mantras from millennia earlier, showcasing a robust decimal structure:

Which gives the values of 10^0 to 10^12. Please note that the value of 10^0 is given as “1” in the sequence. This is not a rare or strange reference from Veda.

Another mantra invokes:

“Oh Lord Agni! Prostrations to you once, twice, thrice, four times five times, ten times, hundred times upto thousand times and unlimited number of times”.

This reflects a clear numerical progression. In the Chamakadhyaya of Krishna Yajurveda, the mantra

gives two sequences of numbers VIZ., 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, 31 And 4, 8,12, 16, 20, 24, 28, 32, 36, 40, 44, 48.

The first sequence lists odd numbers from 1 to 31. The second isn’t mere even numbers but follows a pattern where x_n + x_{n+1} = y_1, with x from the first sequence and y from the second (e.g., 1 + 3 = 4; 3 + 5 = 8, up to the 12th term). Vedic texts also detail cosmological phenomena, such as in the Nakshatreti Prakarana of Yajurveda and Rigveda, underscoring advanced mathematical application.

Mathematical Sciences in Post-Vedic Literature

As we transition to post-Vedic literature, mathematics appears prominently in four key areas:

- The Sulba Sutras

- Vedanga Jyotisha

- Chandas Sastra

- Tantra

These form part of the six Vedic auxiliaries (Vedangas), as noted:

these are the six Auxiliaries to Veda – so say the wise ones

Among them, Sulba Sutras integrate with Kalpa; Vedanga Jyotisha encapsulates time and celestial science; Chandas governs poetic meters; and Tantra simplifies rituals for broader access.

In application:

- Sulba Sutras employ math for altar constructions of various shapes.

- Jyotisha relies on calculations throughout.

- Chandas uses permutations for metrical arrangements.

- Tantra applies geometry to create Yantras representing divine energies.

Grasping Vedic mathematics requires delving into these, though they’re not pure math texts—they embed formulas contextually.

Geometry as the Language of Reality

Vedic mathematics views numbers and lines as interchangeable realities.

- A point (bindu) represents zero dimension

- A line represents unity

- A square embodies multiplication

- A cube expresses dimensional expansion

For instance: The number 1 is a unit-length straight line.

- 1 + 1 is a two-unit line.

- 1 – 1 is a point (Bindu).

These represent one-dimensional segments. However, 1 × 1 = 1 requires a square. 1 ÷ 1 = 1 reverts to a line, while 1 × 1 × 1 = 1 demands a cube—multiplication escalates dimensions.

Though we limit space to three dimensions, Vedic math acknowledges more. Note: (-1) × (-1) = +1 numerically equals 1 × 1, but spatially they’re akin yet distinct. Thus, √1 yields ±1 (two values), and ∛1 produces three: 1×1×1, -1×(-1)×1, 1×(-1)×(-1).

Thus, as numerical operations increase, spatial dimensions multiply. Negative values, roots, and geometrical symmetry were understood not merely algebraically—but spatially.

|  |

A profound sutra by Śrī Kalyāṇānanda Bhāratī states:

A spoken number is inferior to a symbol,

a symbol is inferior to a numeral,

and a numeral is inferior to a line in space.This means, as compared to the word “one”, the representative letter “x” is better; compared to this, the symbol”1” is better; and compared to this, the line on the “ox” axis is better.

This dual view of numbers and space enabled streamlined techniques. Kshetra Ganita (spatial math) subdivides into Jyamiti (geometry), Trikonamiti (trigonometry), and Graha or Gola Ganita (spherical math).

Eminent Figures in Vedic Mathematics

Ancient luminaries like Naarada, Kapila, Bodhayaana, Aapastamba, and Lagadhaa pioneered Vedic math. Medieval masters include:

- Aaryabhatta (5th Century A.D.)

- Varaahamihira (6th Century A.D.)

- Brahmagupta (7th Century A.D.)

- Sreedhara (8th Century A.D.)

- Mahaaveera (9th Century A.D.)

- Bhaaskara (12th Century A.D.)

|  |  |

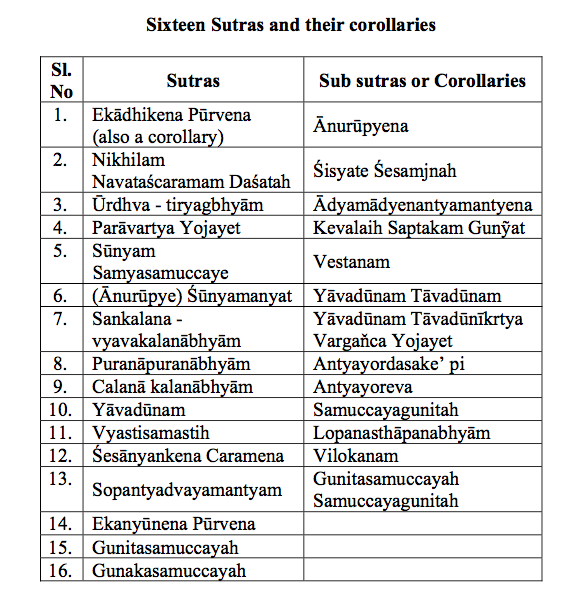

These scholars innovated teaching methods, though sometimes diverging from pure Vedic approaches. In modern times, Jagadguru Bharati Krishna Teertha of Dwaraka Sankaraachaarya Peetha revitalized 16 core Vedic sutras in his 1965 publication “Vedic Mathematics.” These formulas simplify diverse branches, astonishing global experts with their elegance over conventional methods. Today, this system gains international acclaim.

Sulba Sutras In Glimpse & Conclusion

Sulba Sutras aren’t standalone geometry manuals; they guide Vedic rituals, particularly Yagnas and Yagas. They outline altar (Yagna Vedis) and hall (Yagna Saalas) constructions in shapes like rectangles, squares, triangles, circles, and semicircles.

Key features:

- Instructions target lay workers, avoiding complexity.

- “Sulba” means rope; constructions use only rope and scale—no protractors or compasses.

- They enable feats like equating areas of squares to circles using basic tools.

- They approximate values like π, √2, √3.

These sutras, authored by sages like Apastamba, Bodhayana, and Satyaashaada, showcase astonishing ingenuity, offering glimpses into ancient geometric mastery that rivals modern precision.

In summary, Vedic geometry isn’t merely calculation—it’s a harmonious blend of intellect and cosmos, inviting us to rediscover its elegance in today’s world. For those delving deeper into ancient Indian mathematics or Sulba Sutras, this foundation paves the way for profound exploration.