Ancient Indian science is often discussed through two opposing and equally flawed lenses. One view claims that all possible knowledge already existed in the Vedas and only awaits symbolic decoding. The other insists that India possessed no scientific understanding until external civilizations introduced it. Both positions oversimplify history and obscure how knowledge actually evolves.

Scientific understanding, like a nyagrodha (banyan) tree, grows organically over time. Each generation inherits experiential knowledge, refines it, and adds new insights. Modern science is not the product of a single revelation but the cumulative outcome of thousands of years of observation, reasoning, and transmission. Ancient Indian science should therefore be approached not as a complete and final system, nor as a primitive void, but as an early and foundational phase in a long continuum of human inquiry.

This perspective allows us to search for the original conceptual seeds of Indian scientific thought—simple yet profound ideas that later matured into sophisticated systems. Ancient knowledge was not expected to mirror modern complexity. Just as aviation did not emerge instantly from the potter’s wheel, advanced technology cannot be retroactively imposed on antiquity. While ancient thinkers were capable of imaginative speculation, their science remained grounded in observation and available tools.

Observation Without Instruments: The Foundations of Early Indian Astronomy

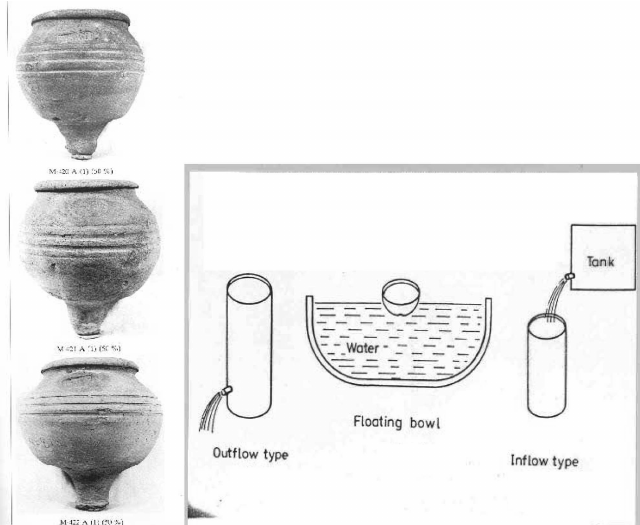

Unlike modern astronomers, ancient Indian observers had no telescopes or advanced measuring instruments. There was no awareness of galaxies, cosmic expansion, or stellar parallax. Yet, through disciplined naked-eye observation and simple devices such as the shanku (gnomon) and ghatikapatra (water clock), they identified key celestial patterns.

By tracking the Sun, Moon, and stars, early astronomers discovered regularities that governed time, seasons, and ritual life. These observations formed the basis of one of the world’s earliest systematic calendrical traditions—an achievement that deserves evaluation on its own historical terms.

Historical Perspective and the Question of Origins

Debates about Indian antiquity often swing between two extremes. One school compresses Vedic culture into a narrow post-1500 BCE timeframe, based on linguistic similarities between Sanskrit and European languages and the presumed Aryan invasion narrative. Another stretches Indian history across vast mythological cycles spanning millions of years.

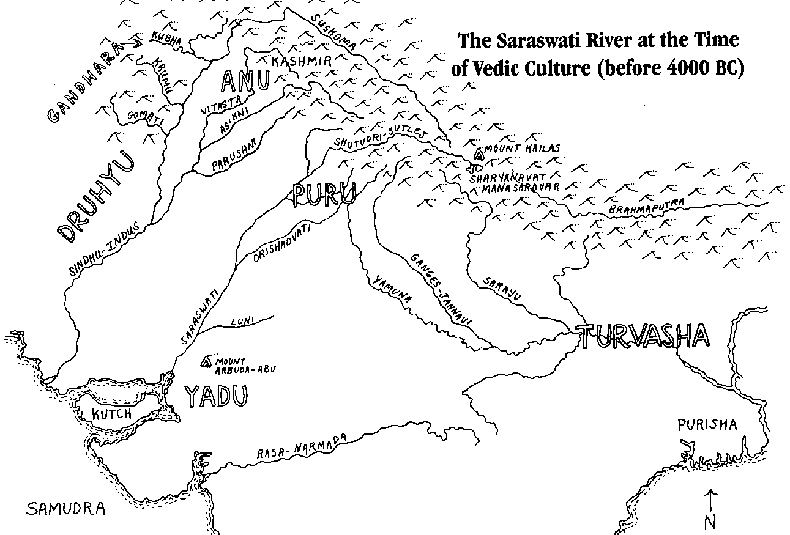

A balanced historical approach suggests neither compression nor exaggeration. Linguistic research has shown strong affinities between Sanskrit and ancient Mesopotamian languages such as Sumerian and Akkadian, indicating deep and complex cultural exchanges rather than simple migration models. Moreover, Vedic literature shows no memory of an external homeland; instead, it reveres Indian rivers—especially Saraswati—with intimacy and precision.

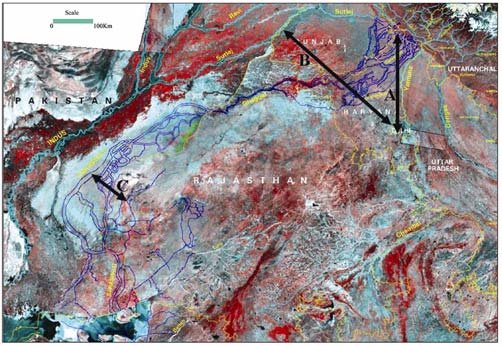

Geological and satellite studies reveal the dried riverbed of the Saraswati across present-day Rajasthan, supporting textual descriptions of a once-mighty river system that declined around 200 BCE. Many so-called Indus Valley sites are located along this ancient river, suggesting continuity rather than displacement.

Climatological evidence also matters. Before roughly 10,000 BCE, prolonged glacial conditions made large-scale settlement impossible. Agriculture and river-based civilizations emerged only after climatic stabilization. Astronomical references embedded in early calendrical systems, however, allow reconstruction of sky positions dating back to approximately 7000 BCE, offering a scientific—not mythological—time depth for early Vedic culture.

|  |

The Evolution of the Vedic Calendar System

The Indian calendar did not appear fully formed. It evolved through observation, correction, and refinement over millennia.

The earliest system was a ritusamvatsara, a seasonal year anchored to the Sun’s northward (Uttarayana) and southward (Dakshinayana) movement. A schematic year of 360 days—twelve months of thirty days—was adopted for ritual purposes. This structure is described in Vedic texts through the Gavamayanam sacrifice, a year-long ceremonial cycle beginning at the winter solstice.

Over time, discrepancies between the idealized year and actual solar motion became evident. The Sun did not reverse direction exactly at the expected moment, requiring adjustment days used for consecratory rituals. These corrections demonstrate empirical awareness rather than blind ritualism.

|  |

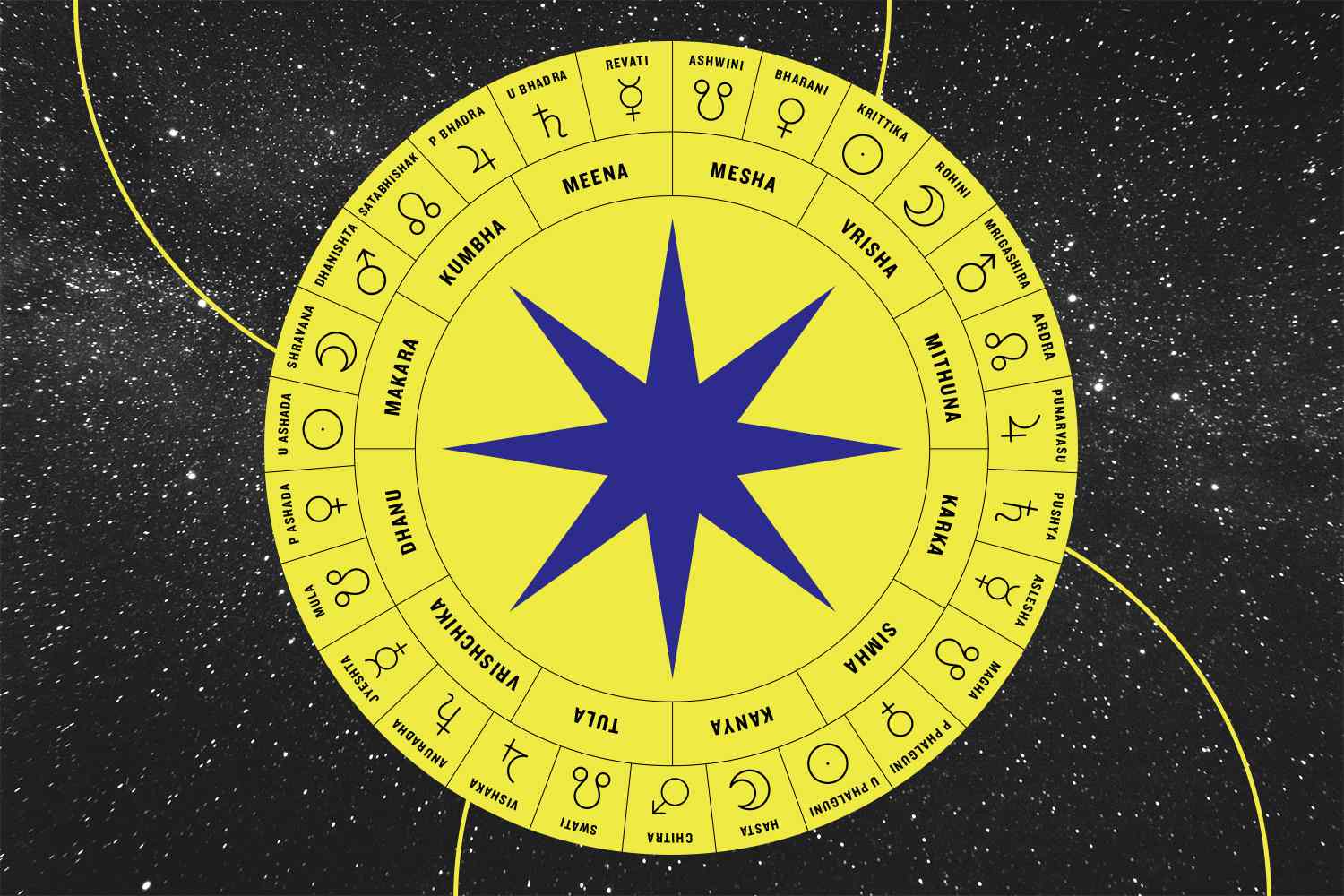

As lunar observation improved, priests recognized that the Moon’s cycle lasted about 29½ days. This led to the concept of tithi, dividing the lunar month into thirty equal parts, and to the structuring of months into Shukla (waxing) and Krishna (waning) phases. The identification and systematic use of nakshatras (lunar asterisms) followed naturally from tracking the Moon’s nightly position along the ecliptic.

Purely solar reckoning proved insufficient for ritual synchronization, while purely lunar reckoning drifted away from seasons. The solution was a luni-solar calendar, refined through carefully timed intercalations.

Early methods added extra days or nights to reconcile lunar months with seasonal cycles. Later innovations introduced adhikamasa (intercalary months) at fixed intervals, and eventually kshaya masa (dropped months) to correct long-term drift. These adjustments were embedded within sacrificial cycles spanning five, fifteen, thirty, and even ninety-five years.

The mathematical rules governing these systems were formalized in Vedanga Jyotish, traditionally attributed to Lagadha around 1400 BCE. This text represents one of the earliest known attempts to codify astronomical computation and calendrical correction.

Transition to Siddhantic Astronomy

With the decline of the Vedic sacrificial system—partly due to philosophical critiques during the Buddhist period—the practical use of early calendrical astronomy weakened. When India later re-engaged with astronomy, it did so through a transformed framework influenced by Babylonian and Greek geometrical models.

This transition marked the rise of Siddhantic astronomy, inaugurated by Aryabhata in the 5th century CE. Mean-motion arithmetic gave way to geometric epicycles, planetary models expanded, and zodiacal signs were formally integrated. The most significant change, however, was calendrical. The year was redefined to begin at the vernal equinox rather than the winter solstice. While this improved sidereal precision, it slowly detached the calendar from actual seasons. Over centuries, festivals drifted noticeably away from their original climatic context—a problem still visible today.

Science, Context, and Continuity

Both ancient Indian and modern Western calendars excel in different dimensions while failing in others. The Gregorian calendar aligns closely with seasons but ignores stellar reference. The traditional Indian calendar preserves stellar accuracy but gradually loses seasonal alignment. Recognizing these strengths and limitations is essential. Ancient Indian science was neither infallible revelation nor borrowed imitation. It was a living, adaptive system, grounded in observation, corrected through experience, and transmitted across generations.

A genuine approach to ancient Indian science does not demand exaggerated claims or dismissive skepticism. It calls for disciplined historical analysis, respect for empirical methods, and an appreciation of how early insights laid the groundwork for later scientific traditions.