Vedic Hinduism, traditionally known as Sanātana Dharma, represents one of the most comprehensive and enduring knowledge systems in human history. Rather than functioning as a single belief structure, it unfolds as a vast, interconnected framework encompassing spirituality, philosophy, science, art, ethics, social order, and inner realization. Its strength lies in its multi-faceted nature, where diverse paths and practices arise organically from a single metaphysical source.

- The Vedas as the Eternal Source of Knowledge

- Unity of Knowledge in the Vishnusahasranama

- The Purpose of Life and the Four Puruṣārthas

- Knowledge, Devotion, and Inner Experience

- Deities, Rituals, and Temples as Inner Technologies

- Lord Natarāja: Dance as Cosmic and Inner Reality

- Music, Sound, and Science in Vedic Thought

- Vedānta, Yoga, and Meditation

- Concluding Perspective

At the heart of this tradition lies a triadic understanding of existence, articulated through the relationship between God (Īśvara or Brahman), the Universe (Jagat), and the individual soul (Jīva). The universe is perceived as an all-inclusive field of beings and natural phenomena, while Brahman is understood as the independent, self-luminous source responsible for creation, sustenance, and dissolution. The individual soul, though appearing limited, carries within it the potential to realize its unity with this supreme reality.

The Vedas as the Eternal Source of Knowledge

The foundation of Vedic Hinduism rests upon the Vedas, revered as Śruti, meaning knowledge that was “heard” or directly perceived by ancient seers in profound states of meditation. These revelations were transmitted orally with extraordinary precision across generations, preserving phonetics, rhythm, and meaning with remarkable fidelity.

The Vedas are regarded as eternal and infinite, addressing fundamental questions concerning consciousness, nature, cosmic order, ethics, and liberation. They are often described metaphorically as the breath of the Supreme Being, emphasizing that all forms of knowledge flow from a single, inexhaustible source.

Over time, this primordial wisdom expanded into a vast corpus of literature—Smṛtis, Itihāsas, Purāṇas, Vedāṅgas, Upavedas, Upāṅgas, and numerous other texts—composed by sages who were regarded not as inventors, but as seers of truth. This immense body of knowledge is traditionally represented as an inverted tree, with its roots in Brahman and its branches manifesting as diverse disciplines of human understanding.

The infinitely expansive Vedic literature includes:

- Smritis (codes of conduct by rishis like Manu, Yajnavalkya, and Parashara)

- Itihasas (epics like Ramayana by Valmiki and Mahabharata by Vyasa—often called the “fifth Veda” for illustrating Vedic principles through relatable stories)

- Puranas (instructive narratives expanding on history and philosophy)

- Upavedas (applied sciences: Ayurveda for health, Dhanurveda for military arts, Gandharvaveda for music and arts, Arthashastra for economics)

- Vedangas (six auxiliaries: Shiksha for pronunciation, Kalpa for rituals, Vyakarana for grammar, Nirukta for etymology, Chandas for prosody, Jyotisha for astronomy)

- Upangas (philosophical Darshanas: Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Sankhya, Yoga, Purva Mimamsa, Uttara Mimamsa/Vedanta)

Unity of Knowledge in the Vishnusahasranama

The integrative vision of Vedic Hinduism is explicitly affirmed in the Vishnusahasranama, where all domains of knowledge and action are traced back to a single divine source. A celebrated verse declares:

Yogo jñānam tathā sāṅkhyaṁ vidyā śilpādi karma ca

Vedāḥ śāstrāṇi vijñānam etat sarvaṁ Janārdanāt

This verse conveys that yoga, philosophy, analytical systems, arts, craftsmanship, ritual action, the Vedas, scriptures, and scientific knowledge all originate from Janārdana, a name signifying the Supreme Reality. The implication is profound: spiritual wisdom and empirical knowledge are not separate pursuits but complementary expressions of the same underlying truth.

In this worldview, vijñāna (applied or scientific knowledge) is understood as the outward manifestation of jñāna (spiritual insight). The sages who attained inner realization did not withdraw from the world; instead, their realization naturally expressed itself through advancements in science, art, music, architecture, and social organization.

The Purpose of Life and the Four Puruṣārthas

The practical orientation of Vedic Hinduism is articulated through the fourfold aims of human life (Puruṣārthas):

- Dharma – understanding and living according to universal and ethical principles

- Artha – acquiring material means necessary for responsible living

- Kāma – fulfilling rightful desires in harmony with Dharma

- Mokṣa – liberation through self-realization and freedom from limitation

These aims are not mutually exclusive; rather, they form a progressive framework guiding individuals from material engagement toward spiritual fulfillment. Life is given meaning not merely through external success, but through alignment with inner truth.

The authority of this framework rests on the testimony of innumerable sages who attained realization and demonstrated that spiritual enlightenment is the ultimate purpose of life, characterized by ānanda (bliss) and mukti (liberation).

Knowledge, Devotion, and Inner Experience

Vedic Hinduism emphasizes that true knowledge must culminate in direct realization. Intellectual understanding alone is incomplete without experiential insight. Hence, the tradition integrates jñāna (knowledge), bhakti (devotion), and karma (action) as complementary paths rather than competing doctrines.

A realized sage describes spiritual knowledge as that which enables one to merge into the light of the Ātman, just as a river merges into the ocean. From this realization flows not escapism, but creative engagement with the world. Science, arts, and culture are viewed as natural expressions of inner awakening.

Deities, Rituals, and Temples as Inner Technologies

The many deities, rituals, icons, and temples of Vedic Hinduism are not arbitrary constructs, but carefully designed means for internalizing subtle spiritual principles. Deities represent specific dimensions of consciousness, while ritual actions engage the senses to stabilize and refine the mind.

A vigraha (icon) functions as a symbolic interface between the devotee and the indwelling divine presence. Similarly, the Hindu temple is conceived as a yogic representation of the human body, where architectural elements correspond to inner centers of awareness. The sanctum (garbha-gṛha) represents the crown of consciousness, reminding seekers that the true pilgrimage is inward.

Life-cycle rituals (saṁskāras)—from birth to education, marriage, and beyond—serve to awaken, nourish, and purify the mind, preparing it for higher realization. Festivals and communal practices preserve cultural continuity while reinforcing spiritual memory.

Lord Natarāja: Dance as Cosmic and Inner Reality

One of the most profound symbols in Vedic Hinduism is Śiva as Naṭarāja, the cosmic dancer. All movement, transformation, and rhythm in the universe are perceived as expressions of an eternal, unchanging substratum.

This vision is beautifully captured in the following Sanskrit invocation, which must be preserved explicitly:

Om namo Natarajaya shudddha jnana svaroopine

Bhaktanam hridaye nityam divyam nrityam prakurvate

This verse proclaims that Lord Natarāja, whose very form is pure spiritual knowledge, performs the eternal divine dance continuously within the hearts of devotees. The dance is not merely cosmic—it is an inner yogic process.

In this symbolism:

- The drum represents creative rhythm (prāṇa)

- The fire signifies dissolution and transformation (apāna)

- The serpent symbolizes awakened kuṇḍalinī energy

- The gesture of fearlessness assures liberation

- The crushed Apasmāra figure represents ignorance—forgetfulness of one’s innate divinity

Spiritual suffering arises from this ignorance; liberation dawns when it is dispelled through inner awakening.

Music, Sound, and Science in Vedic Thought

Vedic Hinduism recognizes sound (śabda) as a fundamental creative principle. Classical Indian music, mantra, and dance arise from this insight. The concept of Śabda Brahman encompasses all vibrations—from audible sound to subtle and cosmic frequencies. The relationship between sound, breath, and consciousness is central to Nāda Yoga, where music becomes a direct path to realization. Saints and composers demonstrated that devotion expressed through sound can lead to profound spiritual experience.

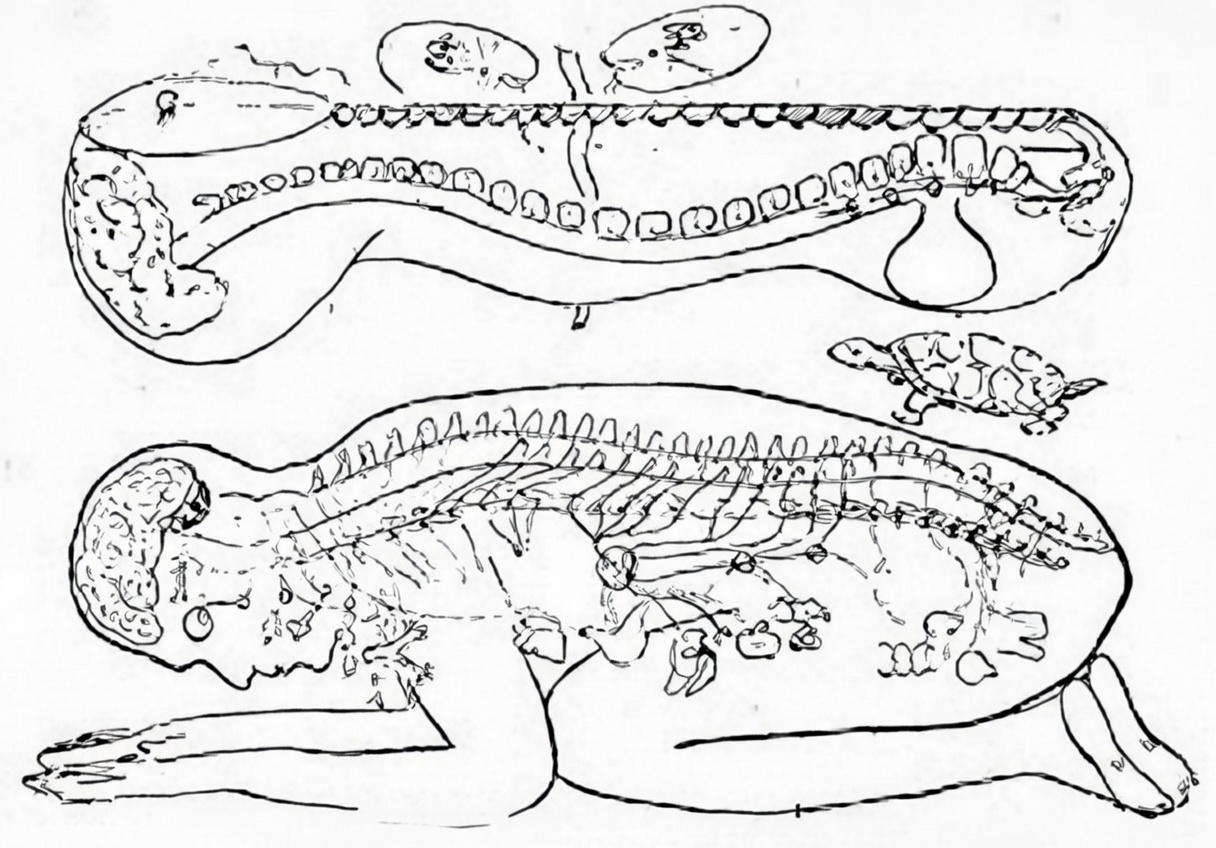

Traditional instruments, rhythmic systems, and chanting methods reflect sophisticated acoustic knowledge. Even ritual objects such as the conch shell are understood as natural instruments producing vibrations aligned with the universal sound Om. Music and dance connect to Nada Yoga. The Veena represents the spinal cord with 24 frets (like 24 Gayatri syllables). Veena-human body analogy.

|  |

The rishis and yogis experienced the various manifestations of the Supreme Being not only within themselves but also in the nature and cosmos. Another illustration is the discovery of a natural instrument namely, conch-shell used for rituals and spiritual practices. The interesting feature is the sharpness of the tone, which is even difficult to obtain in a human-made instrument. The superior sound quality of the tone from a proper conch-shell represents the spiritual vibrations of the universal sound of OM.

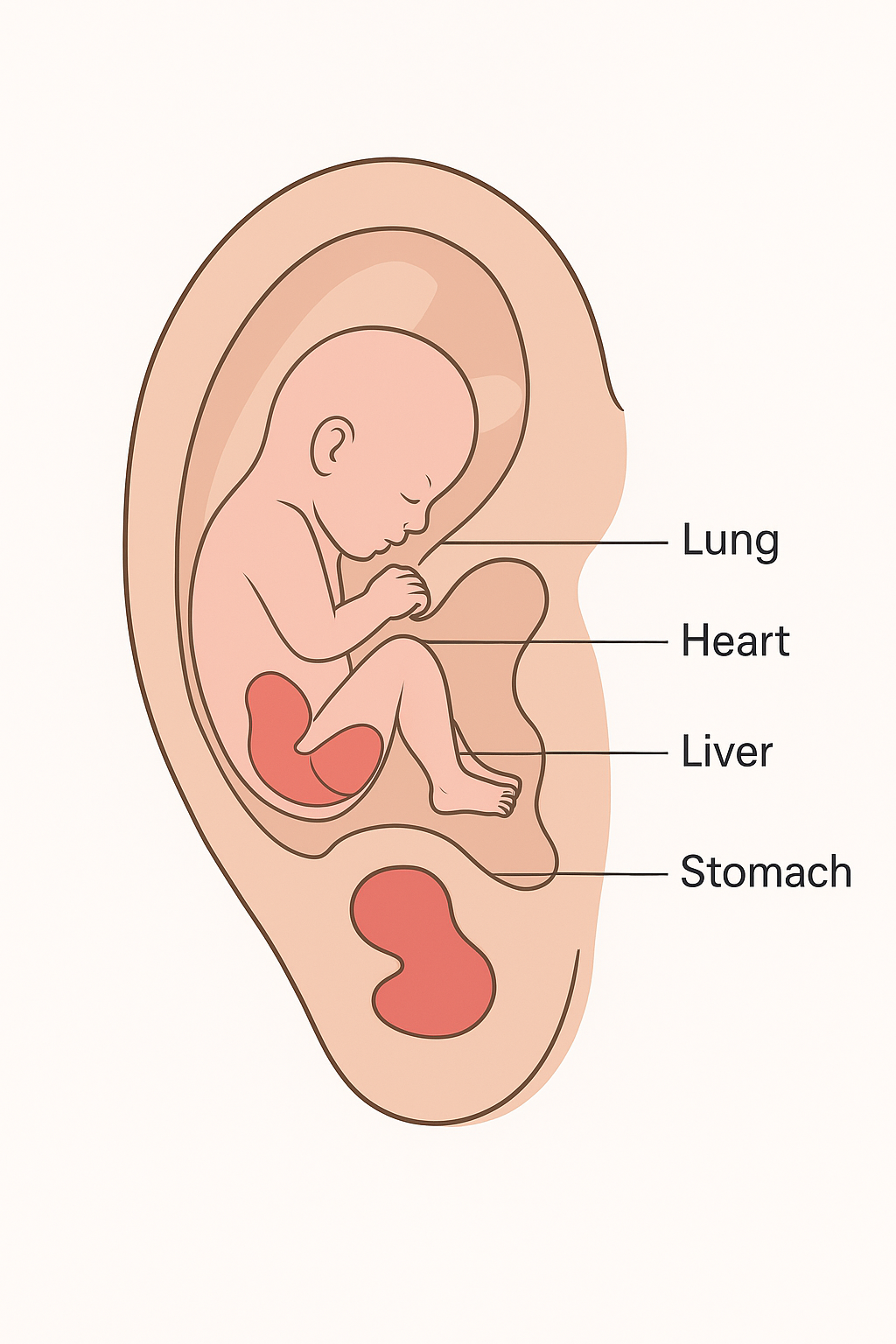

The Garbhopanishad says that an infant in the womb, in its eighth month hears the sound of OM and has the spiritual vision of Light of God. It is for this reason, the Vedic literature says that God is in every being and it is the rediscovery of that vision and knowledge that is needed for spiritual enlightenment.

It is well known that Indian classical music has Vedic origin. The acoustical characteristics such as melodious sound, phonetic quality of letters, proper breaking of words, correct intonation, majesty and proper speed of Vedic chants are precisely transmitted through oral tradition from teacher to disciple. Svaras are common to Vedic chants, music and language. The seven svaras of music are acoustically related to svaras in Vedic chants. It is interesting to note that Vedic chants are effectively played on musical instrument Veena.

The Shabda Bramhan encompasses the full range of vibrations such as infra, audio, ultra and electro-magnetic waves. The Amrita Bindu Upanishad refers to two Bramhans namely ParamBramhan and ShabdaBramhan. Great saints such as Purandaradasa, Tyagaraja etc. have demonstrated that the divine music is a means of spiritual realization. The classical Music in the Vedic Hinduism belongs to the path of yoga namely, Nada Yoga. The treatise of classical music Sangita Ratnakara describes Nada as the union of prana and anala which represents the drum and fire respectively in the hands of Lord Nataraja. The acoustical knowledge of ancient Hindus manifested in several musical instruments. One distinguishing feature of Mridangam and Tabla is interesting. The sounds of a percussion instrument provides the rhythm and not melody. However, the Mridangam and Tabla due to their design produce several harmonic tones, which brings melody to their sounds.

This brings a pleasing quality to rhythmic sounds. It is for this reason the classical music and dance emanating from Vedic origin not only is a spiritual path but also provides joy to mind and senses. shows an interesting scientific experiment referred as Tyndall effect wherein an acoustical tone, when directed on a flame breaks the flame into seven-tongue. In Vishnusahasranama, the seven-tongued fire is referred as a name. This phenomenon of effect of sound or vibrations on flame plays an important role in Vedic yajnas. The sacred fire represents the god or goddess worshipped in a yajna. Thus one can see that the Vedic literature encompasses universal phenomena in nature and cosmos. The Vedic rishis have the abilities of spiritual and scientific insight along with saintly qualities. It is the pursuit of truth objectively by rishis that brought multi-faceted nature to Vedic Hinduism and has made it relevant and useful for all seekers in the past, present and future.

Vedānta, Yoga, and Meditation

It is well known that Vedanta, yoga and meditation have become very popular around the world. However, it is to be noted that they have their source in the eternal Vedas and Vedic Hindu literature. Vedanta refers to not only ending portions of the Vedas but also the essence of the Vedas that emphasize the spiritual knowledge (Jnana). Vedanta deals with the relationship between the God, universe and individual soul. Although there are several Vedantic approaches such as Advaita, Vishishtaadviata, Dvaita etc., they all refer to the Vedas as the transcendental authority and Bramhan as the Independent and Ultimate Truth (Bramha Satyam). Important qualities such as devotion, compassion, forgiveness etc are emphasized for spiritual development.

The need for an acharya or guru is essential in understanding and practice of scriptural guidelines. The important role of karma has to be understood. Thus Vedanta through the Prasthanatrayi, namely Upanishats, Bramhasutras and Bhagavadgita has become the universal and eternal philosophical foundations of Vedic Hinduism. The Bhagavadgita is a shastra (scripture) for both Bramhavidya and Yoga. It is important to note that yoga and meditation have their roots in Vedas and Vedic literature. Vedanta and yoga are the theoretical and practical aspects in the pursuit of realization of Bramhan. The sole purpose of yoga is the realization of original and normal state. Yoga is not merely restricted to poses and acrobatic postures with impressive demonstrations.

The Katha upanishad, Bhagavadgita and Patanjali’s yogasutras are some of the important major references on yoga. It is to be noted that the Ashtanga Yoga of Vedic Hinduism is a systematic approach to reach the spiritual goal of original and normal state of bliss. Ashtanga yoga means eight-limbs of the yoga. Meditation is the seventh step in this approach. The eight-fold Ashtanga yoga briefly consists of

- Yama (self-control) and Niyama (disciplines) dealing with practices related to physical and mental disciplines.

- Asana deals with the practice of physical postures integrating the flexibility of the body and breathing patterns.

- Pranayama deals with the control and regulation of Prana or vital forces.

- Pratyahara deals with the practice of withdrawing the consciousness from the multiplicity of thoughts and directing it toward the inner-self.

- Dharana deals with the development of the ability of the mind to focus and contain a sacred object.

- Dhyana is the meditation or continuous concentration on the sacred object.

The nature and quality of the object of meditation is extremely important. The continuous concentration is compared to that of an unbroken flow of oil and non-flickering flame of a lamp. These seven steps lead the seeker to Samadhi referring to the level of original and normal state and super-consciousness. The order mentioned in this Ashtanga yoga is important. A yogi who has realized and is established in this original and normal state is able to provide genuine guidance as a sadhguru or acharya to the sincere and devoted seeker.

Ashtanga yoga through its scientific and practical approach deals with all aspects of human development such as physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual development. In the words of a seer-yogi Sriranga Sadhguru, ” The customs and habits, the dress and ornaments, the manners and etiquette, the conceptions of right and wrong and of good and evil, the learning, literature and the various arts like music, the political thoughts, views regarding all action and the consecratory ceremonies, etc., of the Indians (Bharatiyas) are all permeated like the warp and woof by Ashtanga Yoga.

Concluding Perspective

Vedic Hinduism has endured across millennia not by resisting change, but by adapting without losing its inner coherence. In an age of technological advancement and global connectivity, humanity continues to face fundamental challenges—conflict, inequality, ecological imbalance, and existential unrest.

These challenges cannot be resolved by external progress alone. They require inner maturity, ethical clarity, and spiritual insight. The multi-faceted structure of Vedic Hinduism offers precisely this integration, making it a living tradition capable of guiding humanity across past, present, future, and beyond.