Conclusion

This article on the Poet in Vedic Aesthetics continues directly from Part 101 and should be read in that sequence for conceptual continuity. What emerges most strikingly at this concluding stage is the clear discrepancy between the poet’s former self and his transformed being. In Dīrghatamas, this transformation becomes conspicuous. He decisively shrugs off his earlier self, even though he cannot fully explain the inner dynamics that govern this change. This conclusion on the poet in Vedic aesthetics brings together insights from the Rig Veda, Atharva Veda, and Sanskrit poetics.

- Conclusion

- Language, Syllable, and the Abode of the Gods

- Poet and Critic: The Dissolution of Difference

- Suggestion, Meaning, and the Zone Beyond Logic

- Sarasvatī: Muse, Mother, and Source of Knowledge

- Brihaspati and the Divine Poet

- Poethood as Spiritual Attainment

- Language, Mantra, and Poetic Craft

- Wonder, Transformation, and Inner Wealth

- Creation, Freedom, and the Self-Creating Poet

- The Poet as Seer

- Final Vision

Importantly, the split within the poet’s personality does not move in a single direction. Rather, it unfolds across multiple dimensions. The poet’s consciousness turns toward the ultimate truths of existence, whereas the ordinary individual gravitates toward the prosaic order of the external world—the world that is too much with us, getting and spending. Dīrghatamas exemplifies this duality when he refers to himself using both the singular and the dual, signaling a divided yet integrated poetic self.

Language, Syllable, and the Abode of the Gods

For the Vedic poet, the ṛks and syllables of poetry constitute the supreme abode of language. The Atharvanic poet functions as the purohita—the priest of kings—who wrestles against the messengers of Yama when they come to claim human life, boldly declaring himself the brahmacārin of Mṛtyu.

Unlike ordinary language, which merely corresponds to objects in the experiential world, poetic language establishes itself as the true language, the very space where the gods reside:

“The undying syllable of the song is the final abode where all the gods have taken their seat.”

(1.164.39) (O’Flaherty 1994:80)

From this follows the crucial importance of understanding syllables, for such understanding sustains the relationship between poetic language and divine presence. Through poetry, human beings can achieve communion with the gods. Moreover, the poet endowed with imagination (pratibhā) shares an aesthetic sensibility with the ideal critic—the sahr̥daya or rasika.

Poet and Critic: The Dissolution of Difference

In Dīrghatamas, the distinction between the poet who creates and the critic who understands collapses entirely. Both converge in a single consciousness. This insight becomes clearer when he juxtaposes the concepts of kṣara and akṣara. Kṣara denotes what decays or flows away, whereas akṣara signifies what is indestructible. This contrast reflects the relation between the empirical and the transcendent, the conditioned and the unconditioned.

Language alone can articulate the transcendent world, while the world of experience remains rooted in it. When Wordsworth speaks of “unknown modes of being” in Tintern Abbey, he unknowingly echoes what Dīrghatamas had already perceived millennia earlier:

“Speech was divided into four parts that the inspired priests know. Three parts, hidden in deep secret, humans do not stir into action; the fourth part of speech is what men speak.”

(1.164.45) (O’Flaherty 1994:80)

The poet, endowed with kavi pratibhā, alone moves freely across all four levels of speech. He shapes language so that the unknown becomes known.

Suggestion, Meaning, and the Zone Beyond Logic

This insight finds support in later Sanskrit theory. The Agni Purāṇa affirms that words gain primacy in śāstra, meaning in itihāsa, and suggestion in poetry. In Dhvanyāloka, apparent meaning dissolves gently into suggested meaning, revealing deeper aesthetic truth. Rabindranath Tagore captures this intuition poetically:

adhara madhuri dharaci chanda bandhane

I have held the ineffable beauty in the prison house of rhythm.

The Vedic poet commands precisely this zone of meaning, where beauty surpasses logical discourse.

Sarasvatī: Muse, Mother, and Source of Knowledge

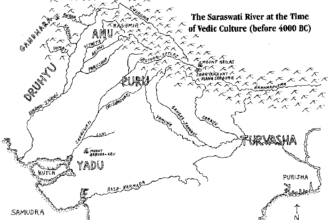

One of Dīrghatamas’s major hymns addresses Sarasvatī, the river goddess and the sole Muse of Indian poetic theory. While the Greeks spoke of nine Muses, Indian aesthetics recognizes one. Sarasvatī signifies both a river and a goddess. The Vedas praise her as the greatest of rivers and mothers—nanditame, ambetame.

As a goddess, Sarasvatī incarnates Brahmavidyā, sacred knowledge itself. She energizes the intellect, purifies reason, rewards worship, and inspires noble action. In the Sarasvatī valley, Aryan civilization first flourished. The poet identifies himself as her child:

“Your inexhaustible breast, Sarasvati that flows with the food of life… bring that here for us to suck.”

(1.164.49) (O’Flaherty 1994:81)

Unlike a human mother’s nourishment, Sarasvatī’s sustenance remains eternal.

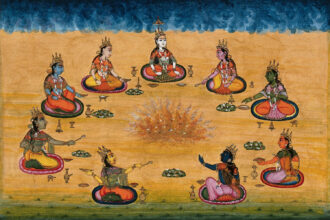

Brihaspati and the Divine Poet

The argument remains incomplete without Bṛhaspati (Brahmaṇaspati), the lord of poetry and pathikṛt—the path-preparer. Symbolically described as possessing seven mouths and seven songs, he embodies poetic wisdom. While several gods are described as kavi in the Atharva Veda, Brihaspati appears uniquely human in origin, later deified for extraordinary poetic achievement.

Historically, poet and priest were united in one person. The poet functioned as the ambassador between gods and humans, hence earning the title seer. Brihaspati thus combines divine and human identities, revealing that true poetry is inseparable from joy and immortality.

Poethood as Spiritual Attainment

Atharvan exemplifies this ideal. Varuṇa gifts him a speckled cow—kavitā-śakti. When asked what made him a poet, Atharvan answers that poetry granted him omniscience. Poethood here is not craft alone but spiritual realization.

Even Yama, later known as the lord of death, appears in the Rig Veda as the pathfinder to immortality, discovering wisdom in the company of poets. Power and wisdom unite, disproving any notion of Vedic poetic effeminacy. Heroism in Vedic culture demands courage to penetrate darkness and emerge with beauty transformed into poetry.

Language, Mantra, and Poetic Craft

When language enters the true poet, it becomes mantra or brahman. Poetry in the Atharva Veda appears as Manīṣā, Saṃsā, Gāthā, and Gir. Agni responds to uktha, Varuṇa blesses stotra, and Indra approaches through dhī.

The poet ceases to be a mere composer and becomes a seer of mantra. Like the Rbhus forging a chariot or a ploughman smoothing furrows, the kavi fashions kāvya-śarīra with precision and beauty:

“Inspired with poetry I have fashioned this hymn of praise for you… as the skilled artist fashions a chariot.”

(Rig Veda 5.2.11) (O’Flaherty 1994:103)

Wonder, Transformation, and Inner Wealth

Sanskrit poetics terms this transformation Atiśayokti—the wondrous blooming of language into poetry. Only the poet reaches the inner tissues of language. Brihaspati assures that one who realizes poetic beauty remains protected.

The difference between poets lies not in possession of language but in depth. All have water, but only some lakes allow full immersion. The true poet emerges with the entire treasury of beauty, guided by insight that unites religion, philosophy, science, and art—thus becoming a civilizational leader.

Creation, Freedom, and the Self-Creating Poet

Brihaspati sings the gods into existence like a smith blowing wind through bellows. Creation arises de novo. Poetry creates not only the gods but the poet himself. No causal explanation accounts for poethood. Freedom defines the poet.

Patañjali’s inward vision, Bhartṛhari’s Śabda-Brahman, and the Vedic understanding of brahman as poetry converge here. In the Rig Veda, brahman (neuter) means poetry; brahmana (masculine) means poet. Only later does the Upaniṣadic Absolute emerge.

The Poet as Seer

The Rig Veda honors poets and gods interchangeably:

“aham kavin Usana paśyatāumā”

(Rig Veda 4.26.1)

Poetry here reveals its divine nature. The poet alone perceives the beloved bird:

“The birds that eat honey nest and brood on that tree…”

(1.164.22) (O’Flaherty 1994:78)

Wisdom is the father. Vision (dṛṣṭi), hearing (śruti), and discrimination (viveka) define the ṛṣi. Dīrghatamas, born blind—one in long darkness—emerges into light like Plato’s philosopher leaving the cave.

Final Vision

With darśana, pratibhā, and inner illumination, the poet alone receives the ancient prayer: from darkness to light, from death to immortality.

“The poet fashioned seven boundaries…”

(Rig Veda 10.5.6) (O’Flaherty 1994:118)

Thus concludes the Vedic vision of the poet—not merely as creator of verses, but as seer, pathfinder, and civilizational architect.